There are times when you need a simple rule engine. You of course know that you can use Drools for the job, but that would be too much of an overhead. So what do you do?

You go and try to find something else that does not have too much of a learning curve and also serves the purpose.

In this blog I will talk about one such library that can be used for simple use cases.

Use Case

For my requirement, I had fifteen different variables that decided the outcome. I could have various valid combinations of these. There were also scenarios where two or more of the variables have to occur at the same time – and some negative cases where two variables cannot occur together.

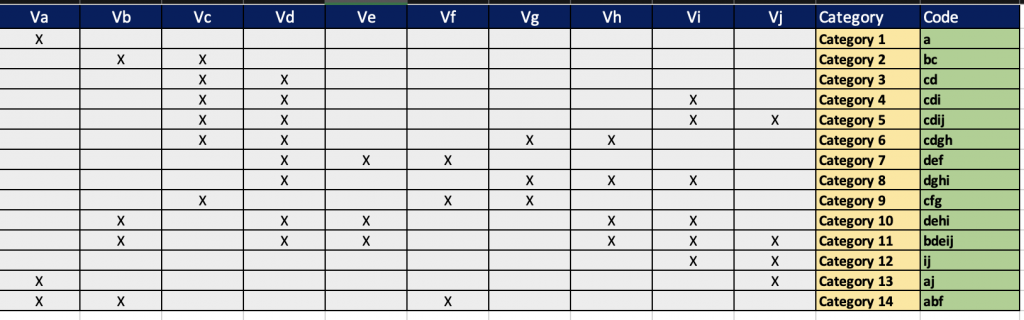

For my convenience I will make it simple. Given below is a spreadsheet that I created with some combinations of ten variables. There is an outcome (Category) associated with each combination. We can have one or more records that match the criteria based on what facts are provided.

The code part we will explain later. If you see the spreadsheet, we have variables Va through Vj. A valid combination can produce outcome Category 1 through Category 14. Setting variables a and j will produce outcomes Category 1 and Category 13.

Theory

Before we go into Easy Rules, I will talk about some basic theory. What is a Rule Engine? A rule engine basically is a software program that takes in some ‘facts’ and runs them through a set of ‘rules’ to reach some results/ conclusions that can trigger an action. You can imaging a rule engine as a large and complex if-then-else query where if asserts the truth from facts and on success then trigger some action.

Facts, very simply put are the conditions that are input to the rule engine. So, if I have defined a Rule as such:

1) When it is Raining ->

Stay Home and Play Indoor Games

2) When it is Sunny ->

Go out and Play Outdoor Games

Let’s add a fact as ‘It is Sunny’. According to the rule given above, the conclusion in this case will be ‘Go out and Play Outdoor Games’. Of course this is a very simple example, but a Rule Engine can handle a very large set of rules.

So, why do we use a rule engine? A rule engine gives us the following advantages,

- Greater Flexibility of Managing Rules: Since rules are defined in one place, it is easier to activate, deactivate, add or remove rules

- Ease of Use: Since rules are defined more like configurations, it is easier to understand and thus easier to update as needed

- Reusable: If we need the same rule in multiple places, we can reuse the rules across multiple decision objects

Easy Rules

According to the developers, Easy Rule is a simple yet powerful Java rules engine providing the following features:

- Lightweight framework and easy to learn API

- POJO based development

- Useful abstractions to define business rules and apply them easily

- The ability to create composite rules from primitive ones

- The ability to define rules using an Expression Language (Like MVEL, SpEL and JEXL)

Easy Rules defines it’s rule using the following Java template,

public interface Rule extends Comparable<Rule> {

/**

* This method encapsulates the rule's conditions.

* @return true if the rule should be applied given the provided facts, false otherwise

*/

boolean evaluate(Facts facts);

/**

* This method encapsulates the rule's actions.

* @throws Exception if an error occurs during actions performing

*/

void execute(Facts facts) throws Exception;

}Facts on the other hand just needs a Name and a Value (both are mandatory).

public class Fact<T> {

private final String name;

private final T value;

}Rules can be defined in a lot of different manners. However, for this project we will use annotation driven approach. I am providing an example how this works below.

POJO Based/ Annotation Driven

@Rule(name = "my rule", description = "my rule description", priority = 1)

public class MyRule {

@Condition

public boolean when(@Fact("fact") fact) {

//my rule conditions

return true;

}

@Action(order = 1)

public void then(Facts facts) throws Exception {

//my actions

}

@Action(order = 2)

public void finally() throws Exception {

//my final actions

}

}A simple POJO can be converted into a Rule using the @Rule annotation as given above.

Implementing Use Case

Ok, enough of theory. Now let’s dive into creating our use case. We create a simple Java projects and include the following two Maven dependencies.

<!-- lombok --> <dependency> <groupId>org.projectlombok</groupId> <artifactId>lombok</artifactId> <version>1.18.36</version> </dependency> <!-- EasyRules --> <dependency> <groupId>org.jeasy</groupId> <artifactId>easy-rules-core</artifactId> <version>4.1.0</version> </dependency>

Lombok just gives us the convenience of creating rudimentary methods for our POJO. The other dependency is for East Rules.

For our Facts, we will create a simple POJO that contains the ten variables we have defined in the spreadsheet above.

package com.suvcodes.rulez.models;

import lombok.Data;

@Data

public class FactVars {

private String va;

private String vb;

private String vc;

private String vd;

private String ve;

private String vf;

private String vg;

private String vh;

private String vi;

private String vj;

}Before we proceed further, let’s a define couple of Utility functions. These will be used for creating the Rules.

package com.suvcodes.rulez.utils;

import com.suvcodes.rulez.models.FactVars;

public class Utility {

/**

* Convert fact into a String sequence

*

* @param v

* @return

*/

public static String checkVar(final FactVars v) {

final StringBuilder bld = new StringBuilder("");

if (v.getVa() != null) bld.append("a");

if (v.getVb() != null) bld.append("b");

if (v.getVc() != null) bld.append("c");

if (v.getVd() != null) bld.append("d");

if (v.getVe() != null) bld.append("e");

if (v.getVf() != null) bld.append("f");

if (v.getVg() != null) bld.append("g");

if (v.getVh() != null) bld.append("h");

if (v.getVi() != null) bld.append("i");

if (v.getVj() != null) bld.append("j");

return bld.toString();

}

/**

* Check if source matches a fact definition

*

* @param key

* @param src

* @return

*/

public static boolean checkContains(final String key, final String src) {

boolean val = true;

for (char ch : key.toCharArray()) {

if (src.indexOf(ch) == -1) {

val = false;

break;

}

}

return val;

}

}What are these functions for? Consider one record in spreadsheet. Category 5 will be set if Facts has variables c, d, i and j all set to true. For an easier compare, when sent that fact, checkVar will convert the FactVar object to cdij and return back.

On the other hand, checkContains will take a key and the variable generated on top, and will try to see if it satisfies the condition. So, if we try to match with c or cdij, it will return a true. However, if we compare with cdig, it will not match

We will use these functions later while creating the rules.

Creating the Rules

Let’s start creating the rules now. I will only create one rule, however, all the other rules follow the same template. I added the rules as Java POJO because that gives me the flexibility of defining the conditions in a more descriptive way. Let’s take a look.

package com.suvcodes.rulez.rules;

import org.jeasy.rules.annotation.Action;

import org.jeasy.rules.annotation.Condition;

import org.jeasy.rules.annotation.Fact;

import org.jeasy.rules.annotation.Rule;

import com.suvcodes.rulez.models.FactVars;

import com.suvcodes.rulez.utils.Utility;

/**

* Dummy Rule

* Va is True

*/

@Rule(name = "Rule Category 01", description = "Rule Category 01")

public class RuleCat01 {

@Condition

public boolean isCategory01(@Fact("input") FactVars factVar) {

return Utility.checkContains("a", Utility.checkVar(factVar));

}

@Action

public void assignCategory() {

System.out.println("Category 01");

}

}In the code above, we have defined Rule for Record 1 in Excel. What we are saying is that this rule evaluates to true whenever Fact has variable a turned on (not NULL). The condition can be as complex as we want it to be. I have kept it simplistic just for this program.

Similarly, we write the other classes and change the key value to following,

- RuleCat02: bc

- RuleCat03: cd

- RuleCat04: cdi

- RuleCat05: cdij

- RuleCat06: cdgh

- RuleCat07: def

- RuleCat08: dghi

- RuleCat09: cfg

- RuleCat10: dehi

- RuleCat11: bdeij

- RuleCat12: ij

- RuleCat13: aj

- RuleCat14: abf

Now that we have the rule in place, we will just need to fire it.

Firing the Rule

First thing first, we will register all the rules we created.

// Define Rules final Rules rules = new Rules(); rules.register(new RuleCat01()); rules.register(new RuleCat02()); rules.register(new RuleCat03()); rules.register(new RuleCat04()); rules.register(new RuleCat05()); rules.register(new RuleCat06()); rules.register(new RuleCat07()); rules.register(new RuleCat08()); rules.register(new RuleCat09()); rules.register(new RuleCat10()); rules.register(new RuleCat11()); rules.register(new RuleCat12()); rules.register(new RuleCat13()); rules.register(new RuleCat14());

Again, we just have a utility method to create the FactVars POJO. Making life simpler for myself. This one just takes a sequence of letters and returns me a FactVars. You can think of this as a reverse of what chekVar function above does.

public static FactVars getCategory(final String str) {

final FactVars vars = new FactVars();

for (final char ch : str.toCharArray()) {

switch(ch) {

case 'a':

vars.setVa("-"); break;

case 'b':

vars.setVb("-"); break;

case 'c':

vars.setVc("-"); break;

case 'd':

vars.setVd("-"); break;

case 'e':

vars.setVe("-"); break;

case 'f':

vars.setVf("-"); break;

case 'g':

vars.setVg("-"); break;

case 'h':

vars.setVh("-"); break;

case 'i':

vars.setVi("-"); break;

case 'j':

vars.setVj("-"); break;

}

}

return vars;

}Now to fire the rules, that is as simple as running the following.

// Define Facts

final Facts facts = new Facts();

facts.put("input", App.getCategory("aj"));

// Define Rules

:::::::

// Fire Rules

final DefaultRulesEngine rulesEngine = new DefaultRulesEngine();

rulesEngine.fire(rules, facts);That’s it. The rule engine will run with the provided fact. But what happens if we want to trigger actions? Or know what is fired? We will use the listener in that case.

// Define Facts

final Facts facts = new Facts();

facts.put("input", App.getCategory("aj"));

// Define Rules

:::::::

// Fire Rules

final RulesEngineParameters parameters = new RulesEngineParameters()

.skipOnFirstAppliedRule(false)

.skipOnFirstFailedRule(false)

.skipOnFirstNonTriggeredRule(false);

final DefaultRulesEngine rulesEngine = new DefaultRulesEngine(parameters);

rulesEngine.registerRuleListener(new RuleListener() {

@Override

public void beforeExecute(final Rule rule, final Facts facts) {

facts.put(rule.getDescription(), "Y");

}

@Override

public void onSuccess(final Rule rule, final Facts facts) {

}

@Override

public void onFailure(final Rule rule, final Facts facts, final Exception e) {

}

});

rulesEngine.fire(rules, facts);

// Check what facts are true

facts.forEach(x -> {

if (!"input".equals(x.getName()))

System.out.println(x.getName());

});In this we have also added something called RuleEngineParameter. The parameter values I set are all defaults, so does not make sense in that context. But I just wanted to show you that you can use the following.

- skipOnFirstAppliedRule :- Only process a single valid rule, ignore rest

- skipOnFirstFailedRule :- Fail as soon as the first rule fails

- skipOnFirstNonTriggeredRule :- Fail as soon as the first rule is not triggered

Now we go to the listener section. beforeExecute will fire for every matched rule (and matched rules only). So, we can put any condition/ action in that block. It can take in the optional Fact parameter and you can manipulate it. In this scenario, I have added the triggered Rule names in the fact object.

So running that will give me the following,

- Rule Category 13

- Rule Category 01

Conclusion

Since we defined POJO based rules, we have the flexibility of writing very complex rule definitions within it. However, each rule still stays independent of each other. We csn use this for creating simple rules in Java. Hope that helps. Ciao for now!